Excerpted from Alcohol Can Be A Gas, Chapter 2

For more than 30 years, I have known of the potential of alcohol fuel (ethanol)—an enthusiasm I shared with my late colleague, master designer R. Buckminster Fuller, who had been involved in ethanol research way back in the ’40s. In 1983, in the waiting room prior to our press conference launching the Alcohol as Fuel television series, Bucky and I discussed the sheer elegance of the alcohol solution.

In design terms, what we were doing was producing a powerfully compact, convenient, nontoxic, liquid form of solar energy that was able to run nearly every device we ever created. Bucky’s delight was palpable. He relished the potential that my book and television series might have on the G.R.U.N.C.H (Gross Universal Cash Heist). Bucky had recently written a book of that title that foretold today’s domination of the world by corporate power.

Since then, I have watched in helpless despair as our country pulled back in its commitment to alternative energy in the 1980s. I have cheered as tremendous advances in ethanol production were made with little help from government, and groaned at the misconceptions that continue to be promoted about ethanol in our popular media.

Most significantly, I have had to feel the burden of responsibility that comes with being a Cassandra, who knew the oil wars were coming, who knew they could be prevented, and who knew the Oilygarchy would get its way and blunder us into ruin. When I became an organic farmer in the early ’90s, I told myself that maybe battles were best fought locally, that the world would come to an alternative energy future in its own time, that the environmental and economic catastrophes would make it imperative. That I should turn away from alcohol fuel and let my garden grow.

But once awakened, one can never again sleep so soundly. Arundhati Roy wrote in her 2001 book, Power Politics, “In the midst of putative peace, you could, like me, be unfortunate enough to stumble on a silent war. And once you’ve seen it, keeping quiet, saying nothing, becomes as political an act as speaking out. There’s no innocence. Either way, you’re accountable.” Maybe I had a destiny to fulfill.

“This is a time for a loud voice, open speech, and fearless thinking.”

—HELEN KELLER

It’s become a sort of heresy to talk about alcohol fuel or any form of alternative energy as a viable way out of our energy dilemma. Debate rages around available technologies and the readiness of our economic system to absorb massive change, but primarily the concern is with practicality. Ethanol, despite its promise, has been trashed in just about every publication and weblog in America.

Rest assured, there is enough land to produce solar energy in many forms, including alcohol, for a world that makes energy-efficient design a priority. We can have a large cooperative cellulose distillery operation in each county, producing ethanol and biomass electricity to keep our essential services running. We can have small integrated farms that produce fuel, food, and building materials. We can eat well on locally produced food and locally processed products. We can even cogenerate our electricity and hot water at our homes using our cars running on alcohol in a pinch, if we are clever enough (see Chapter 24).

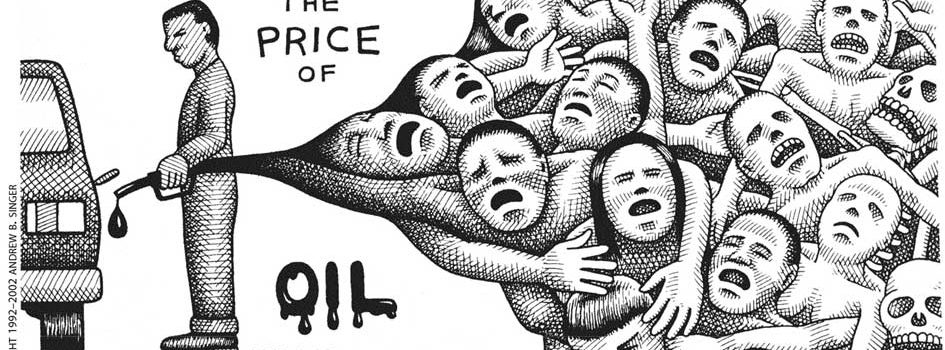

Fig. 2-2

The vituperative bile around fuel alcohol is totally misplaced. Used with a vision that incorporates organic farming—which means shifting totally away from industrial farming methods and implementing sustainable practices—ethanol is an excellent option to solve our energy problems. All of them, if we wish.

Now that you have picked yourself up off the floor, I’ll explain.

I spent nine years as an organic farmer 30 miles south of San Francisco. I had a little over an acre on a 35-degree slope that I terraced and a little over an acre of flat valley bottom. From those bits of land, I produced enough vegetables to provide food for as many as 450 people. The USDA says this isn’t possible. Over time, my organic matter content went from 2% to nearly 22%, the biological equivalent of converting desert sand to deep forest soil. My adobe clay soil went from one inch of topsoil to 16 inches. My loss to insect pests dropped more and more, so that by the fourth year I stopped spending any time worrying about it. I had a very nicely functioning, self-regulating, and self-maintaining ecological system that permitted me to produce huge surpluses of a great diversity of crops and make a decent living.

The key to the success of that long-term experiment was adherence to basic tenets of permaculture. Work with Nature, not against it. Everything is a yield; it’s up to you to realize its value and find what to use it for. Be allergic to any extra work. Put things in the right place in relation to other things. Never fight gravity; it wins. The problem is the solution. Biology is constantly responding to stimulus, “learning” in response, and optimizing itself.

I’ll talk more about the synthesis of permaculture (including organic farming) and ethanol production in future posts, but keep it in mind as we address the myths about alcohol fuel.